|

||

|

On the Road to EU The Tourkokratia - Was it Really That Bad?-Part 1A |

||

|

Athens News Was the 4-century-long Ottoman rule of Greece a burdensome legacy for the nation's overall development? In the first of three articles, historian David Brewer reviews the Tourkokratia at the heights of its power and explains how it was not that bad and even brought some benefits to the Greeks |

||

THE PERIOD of the Tourkokratia is reckoned as lasting from the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453 until the formal recognition of Greek independence in 1833.Many Greeks passionately believe a commonly found version of Greek history that paints the Tourkokratia as a period of unrelieved awfulness. The Greeks are described as enslaved - ipodhouli or en dhoulia. Their children were taken away to serve in theTurkish army or at the sultan's court. The Greeks suffered under constant pressure to abandon their Christian Orthodox religion and convert to Islam. To keep the Greek language alive they had to educate their children secretly. Any protest or revolt was ruthlessly suppressed. Heavy taxation made their lives miserable. The Tourkokratia cut Greece off from the artistic developments of theRenaissance and the intellectual developments of the Enlightenment. Furthermore the Turks in four hundred years failed to bring any improvements to Greece and left nothing of value behind them. |

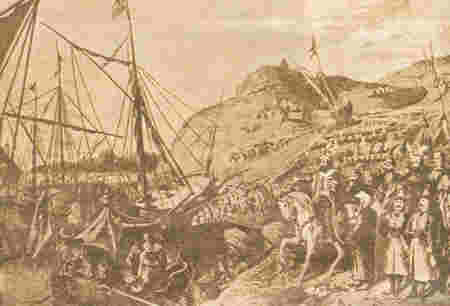

See Also: Turkey and the West: From the Ottomans to the EU - Part 2 The Tourkokratia - Was it Really That Bad? - Part 2A  Sultan Mehmed oversees the successful operation of dragging the Ottoman ships overland from Bosphorus into the waters of the Golden Horn during the final stage of the seige of constantinople on 22 April 1453 |

|

Given that picture, it may seem ludicrous to ask if the Tourkokratia was really that bad. But a closer look at the history provides some unexpected answers. Five conflicts, one in each century, immediately or indirectly affected the conditions of the Greeks and provide the framework of the Tourkokratia story. The first, of course, is 1453, the Turkish capture of Constantinople, the end of the Byzantine Empire, and the Turkish annexation of most of the Balkans including Greece. In the next century, the battle of Lepanto in 1571 brought the crushing defeat of the Turkish navy by a combined fleet from some of the powers of Europe. In 1669 the Turks finally won Crete from her Venetian rulers, and consolidated Turkish dominance of the eastern Mediterranean.1770 was the year of the short-lived Orlov revolt in Greece, instigated by Catherine the Great and named for its Russian leaders, which was quickly and ruthlessly crushed. Finally, in 1821 the Greek war of independence broke out, ending 12 years later with the establishment of Greece as an independent state. |

||

The janissaries - a battalion of flg-bearers sketched Peter Koeck (1502-1550) |

||

The early years The Turks were not the only rulers in Greece during the so-called Tourkokratia. It was not until the mid 1500s, a century after the fall of Constantinople, that the Turks acquired Cyprus from the Venetians, Chios from the Genoese, and Rhodes from the crusading order of the Knights of St John. It was another hundred years before Turkish rule replaced Venetian in Crete. What were conditions in Greece like before the Turks arrived? On 12 April 1204 Constantinople had fallen to the crusaders of the Fourth Crusade, who looted the city and established the so-called Latin empire there. This Latin empire lasted only fifty years, and Byzantine rulers returned to govern a diminished empire for another two centuries. For Greece the Fourth Crusade brought a radical upheaval- the division of the country between rival despots. After 1204 the Peloponnese was ruled for 60 years or so by a crusading family from the Champagne region of France, theVillehardouins, who brought stability and prosperity with them. But this golden age was not to last. The restored Byzantine rulers drove the Villehardouins out of the Peloponnese, and the next two centuries until the Turkish conquest were ones of constant conflict, as invaders from Anjou in France and from Cataluna and Navarra in Spain tried to wrest control of the Peloponnese from the ever-weakening Byzantine empire. Salonika had no golden age, and it was the scene of constant warfare. Salonika was the biggest commercial prize in Greece, lying on the old Roman Via Egnatia linking Constantinople with the Adriatic coast and the west, and also having a fine harbour. After1204 the city was held by one of the leading crusaders, Boniface of Montserrat. Twenty years later it was seized by the despot of the neighbouring region of Ipiros; and then by theByzantines. In the following century it was besieged by Catalans, governed briefly by chaotic commune at the time of the Black Death, taken by the Turks and then taken back by the Byzantines. The Turks finally captured Saloniki their first lasting Greek possession, in 1430, and held it for nearly 500 years. Moreover, the crusaders brought their Catholicism with them. The schism between the Catholic west and Orthodox east had rumbled on for centuries, nominally over doctrinal issues such as the famous filioque controversy - did the Holy Spirit proceed from the Father alone, or from the Father and the Son? But it was really about whether or not the Orthodox patriarch in Constantinople was subject to the rule of the pope in Rome. No longer a remote dispute, the schism had now physically arrived in Greece. Catholic Latin clergy were installed in the cathedrals, though not in the countryside. The former Orthodox archbishop of Salonika wrote of "the stupid and discordant cries of a Latin service ... disturbing good order and holy harmony." This then was the Greece which the Turks acquired in the series of conquests which began in 1430: a once prosperous land, people whose religion was under threat, and a scene of constant and bloody turmoil. The fateful year 1453 and its aftermath It was on Monday, April 2 1453, the day after Easter Sunday, that the first Turkish troops appeared outside Constantinople to begin a two-month siege. The city was the capital of a now shrunken empire, reduced to the despotate of Mistra in the Peloponnese, a few outposts such as the Black Sea port of Trebizond, and the city of Constantinople itself. Constantinople was walled all round, and without these walls the defenders could not have held out for two months. They were heavily outnumbered - 7,000 against 80,000 attackers. One of the besieged wrote, "We are an ant in the mouth of the bear." These defenders were not only, or even mainly, Byzantine Greeks. There were also Genoese under their captain Giustiniani, Venetians, Cretans, and even Turks loyal to the exiled Ottoman prince Orhan. The Byzantines were led by their last emperor, Constantine XI. On 6 April, four days after the Turks first appeared, they began to bombard the western land walls of the city, and the bombardment continued intermittently for six weeks. On the Golden Horn to the north the Turkish fleet tried first to force its way past the protective boom but without success. They then resorted to the fantastic idea of dragging their ships overland over a 200 foot high ridge to relaunch them inside the boom. This amazing operation succeeded, and on 22 April some 70 Turkish ships slid into the waters of the Golden Horn. But skirmishes there between the transported Turkish fleet and the defending Genoese and Venetian ships were inconclusive, and the walls along the Golden Horn were not breached. At this point Sultan Mehmed might have withdrawn and Constantinople might for the moment have survived. The sultan's grand vizier, Halil Pasha, argued that the siege should be abandoned. But more hawkish members of the sultan's court prevailed. The attack was intensified, and Halil Pasha paid for his rejected advice with his life. The end followed two small mischances. Giustiniani, the Genoese captain commanding the defence of the land walls, was lightly wounded. When he went back behind the walls to be treated, his men thought he was running away and they began to flee. Also the smallest gate in the walls was accidentally left unbarred. On 29 May 1453, a date still remembered with sorrow, the Turkish troops poured in, and the three-day sack began, sanctioned by both Christian and Islamic codes of war for a city taken by assault. The emperor Constantine died in the fighting, but his body was never recovered. In the late afternoon of that day the sultan entered Ayia Sophia, the greatest church in the city. A Muslim cleric proclaimed that there was no God but Allah, and the sultan himself made obeisance to the God of his faith. One might have expected that Christianity would now be suppressed, but exactly the reverse happened. The first patriarch under Ottoman rule, Yennadhios, was enthroned within a year of the conquest, and Sultan Mehmed himself handed Yennadhios the robes, staff and pectoral cross of office. The Greeks,like other Christians in the Ottoman empire, were left completely free to practice their religion, under the patriarch's spiritual leadership. The patriarch was now the political as well as the spiritual leader of the Christian Ottoman subjects, responsible for the good behaviour of his flock, and for ensuring that they paid their taxes to the state. All this promised well. But the church was soon undermined for two reasons: Turkish manipulation and money shortage. Intrigues by the Turks led to repeated changes of patriarch: 61 elections from 1595 to 1695. This signifisantly impoverished the church since the patriarchate had to make a substantial payment to the state at each election. State taxation of the patriarchate also - stead increased. By the beginning of the nineteenth- century the church seemed practically moribund, and a disgruntled traveller maintained that orthodoxy was no more than "a leprous composition of ignorance, superstition and fanaticism." Though the church was in a shocking state, it was highly valued by the Greeks. Like any other church, it baptised, married and buried, and provided, a social meeting point. It was a link to the saints, especially the Virgin Mary, their frescos and icons decorated the church walls, and the saints were seen as ever present. In daily life and continuing to work miracles the local priest, the pappas, was. probably the literate person in the community, and represented the villagers to the authorities. A prime value church membership was as a badge of difference from the rulers. Church teaching though did not shape personal behaviour. Morality was governed by traditional codes of honour - on theft, adultery, or killing...rather than by Christian precepts. Some traditional Greek histories suggest that there were forcible or mass conversions to Islam. But the Turks had no incentive to force conversion on Christians and, as a result, lose the poll tax, paid only by Christians. Nor was avoidance of the poll tax a sufficient incentive for the Greeks to convert. They would, it was said, be "selling their souls for a penny worth." Large scale conversion of Greeks seems to have happened only once,and for special reasons, in Crete. |

||

|

Pedhomazoma - the child collection |

||

HCS readers can view other excellent articles by the Athens News writers and staff in many sections of our extensive, permanent archives, especially our News & Issues, Travel in Greece, Business, and Food, Recipes & Garden sections at the URL http://www.helleniccomserve.com./contents.html

All articles of Athens News appearing on HCS have been reprinted with permission. |

||

|

||

|

2000 © Hellenic Communication Service, L.L.C. All Rights Reserved. http://www.HellenicComServe.com |

||